22 Mar Clayoquot Sound, Canada

Laura Loucks

Key Messages

• Collective action in an unsustainable social-ecological system can catalyse a shift towards increased community sustainability when supported with financial resources and appropriate local institutions.

• Cross-cultural knowledge sharing and place-based learning are integral to transforming social-ecological systems at the community level.

• Social innovation can assist with transformation when supported by a network of collaborative organizations with a shared set of principles and a united vision to inspire change.

Community Profile

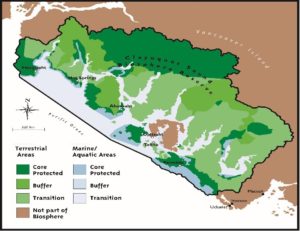

For millennia, the Indigenous Nuu-chah-nulth people have had strong cultural and livelihood connections with the terrestrial, fresh water and marine ecosystems of the west coast of Vancouver Island, Canada. Within this area, Clayoquot Sound is located primarily in the Nuu-chah-nulth Ha’ huulthii (homelands) of Hesquiaht, Ahousaht and Tla-o-qui-aht First Nations, encompassing nearly 350,000 hectares of a complex and globally significant social-ecological landscape (Figure 1).

The ecosystems of Clayoquot Sound are rich in biodiversity and characterized by a large contiguous rainforest canopy of old growth western red cedar and western hemlock covering steep-sided coastal mountains throughout six watersheds.

There are five different species of Pacific salmon which originate from the rivers of Clayoquot Sound and each supports some element of culture, economy and food supply for eight different communities within the region: Hesquiaht, Ahousaht, Opitsaht, Tofino, Estowista/Ty-Histanis, Ucluelet, Hitacu and Macoah.

Figure 1: Clayoquot Sound UNESCO Biosphere region

In 2000, Clayoquot Sound was designated a United Nations Educational Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) Biosphere Reserve. The nomination for the protected area was made after more than a decade of conflict and community action to prevent the logging of old growth coastal temperate rainforests. The key conservation goals of UNESCO Biosphere Reserves are to conserve biodiversity and to safeguard the sustainability of natural and managed ecosystems by uniting communities and nations in peace and cooperation, through education, science, culture and communication (10).

Conservation and Livelihood Challenges

Resource extraction, conflict and collective action

Over the last 50 years, local communities have constantly struggled to assert local access rights to Crown resources and shape government policies for more sustainable resource management practices in fishing and logging. In the forestry industry, unresolved Aboriginal land claims and corporate rights to Timber Forest Licenses were at the heart of unsustainable land use. For example, logging companies commonly built roads along steep mountain slopes, despite the high risk of soil erosion and damage to stream and river habitats. Similarly, large tracts of old growth rainforest were clearcut, causing significant ecological damage without the consultation or consent of the Nuu-chah-nulth Ha’ wiih, who carry the traditional responsibility to preside over and protect the Nuu-chah-nulth Ha’ huulthii(9).

However, in 1982 the affirmation of Aboriginal rights and treaty rights within Section 35 of the Canadian Constitution marked an enormous shift in Canadian Law(5). These rights were further strengthened in the seminal Meares Island Case, which catalyzed a transformation process still underway in Clayoquot Sound(5).

In 1984, a coalition of leaders and residents from Tla-o-qui-aht First Nation and the town of Tofino sought to protect Meares Island, within Clayoquot Sound, from being logged by the MacMillan Bloedel forestry company. The Nuu-chah-nulth Tribal Council claimed the island as part of the traditional territory to which it had Aboriginal title and sought a court injunction against the logging of the Island. Subsequently, the logging company requested their own court injunction against the coalition. In an unprecedented decision, the British Columbia Court of Appeal granted the injunction to the Nuu-chah-nulth based on the irreversible damages of unsustainable forestry practices(5). In the words of Justice Seaton,

“It appears that the area to be logged will be wholly logged. The forest that the Indians know and use will be permanently destroyed. The tree from which the bark was partially stripped in 1642 may be cut down, middens may be destroyed, fish traps damaged and canoe runs despoiled. Finally, the island’s symbolic value will be gone. The subject matter of the trial will be destroyed before the rights are decided”(5, pg.149).

The victory of the Meares Island Case also marked the beginning of the Tla-o-qui-aht assertion of rights and title to the Meares Island Tribal Park, and 10 years of conflict(9). In 1994, in an effort to resolve an escalating environmental campaign, the British Columbia government announced a Scientific Panel for Sustainable Forest Practices in Clayoquot Sound. Through this, the Nuu-chah-nulth principle of hishuk-ish-ts’awalk (everything is one and interconnected) inspired a set of new hybrid protocols designed to respect both traditional ecological knowledge (TEK) and scientific knowledge systems(6). Recommendations of the scientific panel were eventually instituted through watershed management plans that now provide the foundation for adaptive ecosystem management in the region. One plan is in the Indigenous community of Ahousaht, where Chief Maquinna has noted:

“The Ahousaht believe that this is the beginning of a new era, based on recognition and celebration of Ahousaht people and culture, conservation of the world-class forest and marine resources of Clayoquot Sound, and the development of a more diversified, sustainable local economy, including community forestry.”(8)

A recent challenge concerns the decline of fishing and logging livelihoods over the last decade. On the other hand, employment in nature tourism has rapidly grown, and is now one of the main economic forces for West Coast communities, attracting over one million visitors per year(4). However, several warning signs indicate the steady growth of tourism has potentially exceeded the sustainable capacity of many communities within the Biosphere Reserve. For example, the escalating rise in the number of West Coast visitors is strongly correlated with the increased seasonal demand on emergency medical services, increased summer drought vulnerability, lower average income levels and a reduced supply of long-term affordable housing units(4).

Community Initiatives

Today, the principles and protocols established by the Scientific Panel are embodied in local community organizations with new governance models based on the shared desire to build a sustainable future on West Coast Vancouver Island. One such example is the Clayoquot Biosphere Trust (CBT), which is led by a voluntary board of directors, representing all local First Nations and communities within the Clayoquot Sound Biosphere Reserve, with a vision:

“…to live sustainably in a healthy ecosystem with a diversified economy and strong, vibrant and united cultures while embracing the Nuu-chah-nulth First Nations living philosophies of Iisaak, (living respectfully), Qwa’aak qin teechmis (life in balance) and Hishuk ish ts’awalk (all things are connected)”(2).

In monitoring community development trends using a range of sustainability indicators, CBT raised the above-noted tourism issue. Given the potential negative impacts, local leaders worked to identify ways to diversify tourism livelihoods with elements of the knowledge and sharing economy. A new West Coast learning initiative(7) was started, including (i) an initiative to identify community education needs and priorities, involving local organisations, educational institutions and government agencies; (ii) partnerships between organisations throughout the Biosphere region and between municipal and provincial governments, to align job training priorities; and (iii) leveraging of funds within the region to support an education asset inventory(3) and research on the feasibility of education tourism to build local learning capacity and develop a visitor market demand for place-based education(7).

In 2016, a collaboration of the CBT, First Nations, municipal governments, local education organizations and destination marketing organizations, launched the West Coast NEST (Nature, Education, Sustainability, Transformation) to connect people to all current learning opportunities offered in the region, focusing on four key market sectors: university field schools, professional development courses, adult learning and youth learning opportunities.

The vision is to enable all local community members and education-oriented organizations to participate fully in the learning economy, together with visiting learners(7)(Figure 2). By linking learning with tourism, the West Coast NEST is creating a global network of learners who can help catalyze a new local economic opportunity while shifting values towards sustainable livelihoods.

Figure 2: Nuu-chah-nulth Elder Ray Haipee teaching visiting learners.

Nested within the Nuu-chah-nulth values of Iisaak, qwa’aak qin teechmis and hishuk ish ts’awalk, the education tourism initiative is an opportunity to transform conventional tourism to attract a different type of visitor: one who wants to stay longer on the West Coast, learn from local people, experience local culture and contribute to stewardship of this ecologically significant place.

In this manner, local community organizations are working to shift away from an unsustainable tourist ‘consumer’ economy and moving incrementally towards a new ‘conserver’ economy, where broken cultures are restored and damaged SES are re-built. The communities see education tourism as having the potential to support an economic return from visiting learners while expanding local learning opportunities.

Seven principles for education tourism:

1) Attract co-learners: we welcome others to learn with us.

2) Community reciprocity: we share benefits between communities.

3) Local knowledge holders are experts: local people are reimbursed for sharing their knowledge.

4) Learning networks of practice: together, we are creating a culture of learning and collaborative problem solving.

5) Stewardship-in-place: every community has an outdoor classroom and a place to learn from the land.

6) Holistic hands-on learning: we learn best by applied learning and practice.

7) Cultural safety and sharing: we create safe spaces for learning and healing across cultural boundaries.

Practical Outcomes

The West Coast learning initiative has demonstrated innovative solutions for sustainable livelihood challenges. As more organisations contribute to education programme development, education initiatives for local and visiting learners increase, resulting in a broader distribution of economic benefits and sustainable livelihood options. In 2017, for example, 75 educational courses and 356 educational events were offered, over 150 temporary work opportunities were created delivering educational courses, and 712 temporary positions were created to deliver educational events. In 2019, these benefits have expanded to include 320 educational courses, 1,032 educational events, 66 seasonal positions and 2,064 temporary positions.

The West Coast NEST motivates both lateral and vertical connectivity across local communities in the region, as well as organisations who share a vision for higher learning and contribute to sustainable economic diversification. Working within the principles and values of a Nuu-chah-nulth worldview helps to guide a regional vision for higher learning while also supporting a shared culture of place-based stewardship. Likewise, training has been provided for over 40 students of a leadership program, from Nuu-chah-nulth and non-Nuu-chah- nulth communities, who continue to volunteer their time to local community projects.

Local economic development capacity is growing with the following programmes: First Nation Tourism Training certificate, governance training, grant writing workshops, strategic career management training and Critical Incident Stress Management Training in partnership with three First Nations and the Justice Institute of British Columbia.

The measurable benefits from education tourism help to support local municipal government plans and policies to further diversify the tourism economy and invest in sustainable economic development. The town of Tofino, for example, identifies several economic development goals in support of education tourism such as the goal for Tofino to become a centre of excellence in learning, research and development.

In summary, the West Coast NEST is an example of how cross-cultural collaboration, knowledge sharing and place-based learning are integral to transforming SES at the community level. As the number of education opportunities grow, more options for new and innovative forms of sustainable livelihoods naturally unfold, especially when supported by municipal government sustainable economic development initiatives. All these actions, when taken together, help to support the ground swell of social change and transformation underway in the Clayoquot Sound UNESCO Biosphere Reserve.

References

- Austin, M.A., Buffet, D.A., Nicholson, D.J., Scudder, G.G.E. and Stevens, V. (eds.) (2008). Taking Nature’s Pulse: The Status of Biodiversity in British Columbia [online]. Victoria, BC, Canada: Biodiversity BC. Available at: http://www. biodiversitybc.org/EN/main/downloads/tnp-introduction. html

- Clayoquot Biosphere Trust (CBT) (2014a). ‘Vision’. CBT [website]. Available at: https://clayoquotbiosphere.org/about- us/overview

- CBT (2014b). Regional Education Asset Inventory. Tofino, BC, Canada: Clayoquot Biosphere Trust. Available at: https:// clayoquotbiosphere.org/files/file/5d6f46b85bb19/Regional- Education-Asset-Inventory_final.pdf

- CBT (2016). Clayoquot Sound Biosphere Region’s Vital Signs 2016. Tofino, BC, Canada: Clayoquot Biosphere Trust. Available at: https://clayoquotbiosphere.org/research/vital- signs

- Harris, D. (2009). ‘A Court Between: Aboriginal and Treaty Rights in the British Columbia Court of Appeal’. BC Studies162 (Summer): 137–152. Available at:https://commons.allard.ubc.ca/cgi/viewcontent. cgi?article=1181&context=fac_pubs

- Lertzman, D.A. (2010). ‘Best of two worlds: Traditional Ecological Knowledge and Western Science in Ecosystem based Management’. Discussion Paper. BC Journal of Ecosystems and Management 10(3): 104–126. Available at: https://jem-online.org/index.php/jem/article/ download/40/12

- Loucks, L., Thicke, C., Bird, G., White, B. and Harris, R. (2015). Education Tourism Market Development Strategy for the Pacific Rim Knowledge Initiative. Royal Roads University, Sooke, BC. Available at: https://clayoquotbiosphere.org/files/ file/5d6f46888bfc9/2015-Pacific-Rim-Education-Tourism- Market-Development-Strategy.pdf

- Maaqutusiis Hahoulthee Stewardship Society (2017). Ahousaht Land Use Vision. Press Release, 25 January 2017. Available at: http://www.mhssahousaht.ca/news/press- release-ahousaht-land-use-vision

- Murray, G. and King, L. (2012). ‘First Nations Values in Protected Area Governance: Tla-o-qui-aht Tribal Parks and Pacific Rim National Park Reserve’. Human Ecology 40: 385–395. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10745-012- 9495-2

- United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) (2017). Final Report of the Twenty- ninth session of the International Co-ordinating Council (ICC) of the Man and the Biosphere (MAB) Programme. Paris, France, 12–15 June (2017). Available at: http://www. unesco.org/new/fileadmin/MULTIMEDIA/HQ/SC/images/FINAL_29MAB_ICC_REPORT_ENG.pdf

Acknowledgements

Support for this story was provided by the Community Conservation Research Network (CCRN) and the Clayoquot Biosphere Trust (CBT).