08 Jun Koh Sralao, Cambodia

Furqan Asif, Jason Horlings and Melissa Marschke

Key Messages

- The Koh Sralao community work together to safeguard their mangrove forests which form a critical link to their livelihood.

- Community activism concerning coastal resource management issues and resistance to sand dredging contributed to the termination of nearby dredging activities.

- The development of a Special Economic Zone in the provincial capital has provided valuable economic opportunities for young women, contributing to livelihood diversification.

Community Profile

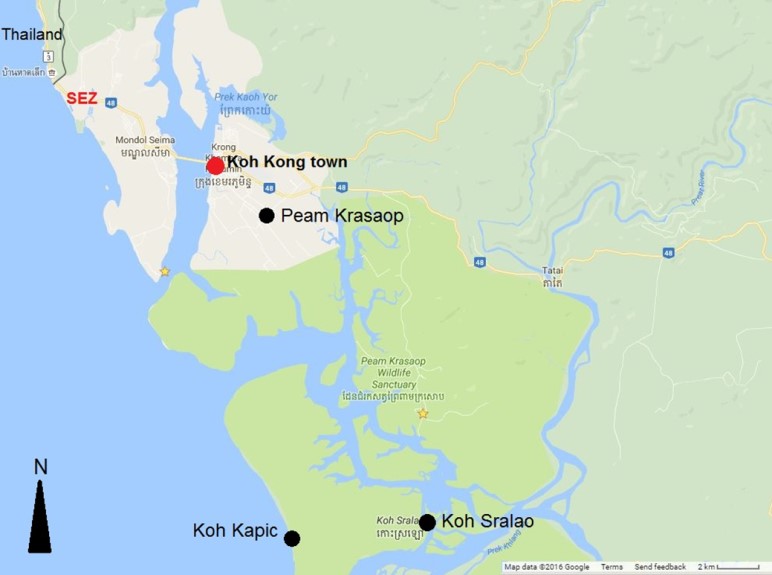

Figure 1: Map showing select fishing villages including Koh Sralao (bottom right) in relation to Koh Kong town and the SEZ. Map: Google (modified by Furqan Asif).

Koh Sralao is a small 300 household mangrove-estuarine fishing village on the southwestern coast of Cambodia (Figure 1), approximately 22 km from the provincial capital Koh Kong. The village is accessible only by boat. Given the remote nature of the community, most goods and products need to be shipped in and out.

Villagers rely heavily on the marine environment, with fish making up the bulk of their dietary protein. The local marine resources have been the source of sustenance and livelihood for many decades. Although the main activity is crab fishing, a diversity of fishing activities are found, including green mussel culture, shrimp and grouper fishing(6).

Local fishers use mechanized boats and gill nets or crab traps to harvest the marine resources in and around the mangrove estuarine area, or within a few kilometers of the coastline. Households work together, with men (sometimes with their wives) going out to fish daily or spending a few days on their boats and women sorting, processing and selling aquatic products to a handful of local traders (aquatic products typically go to the provincial town, and then may move to Cambodia’s capital or into Thailand).

However, sustaining a small-scale fisheries livelihood is challenging(5) and livelihoods have diversified within and beyond the village. For example, households may have family members working (temporarily or permanently) in construction or factory jobs. While this work has typically been in another province, in Cambodia’s capital or in Thailand, there are now wage-labour opportunities particularly for young women in the provincial capital at the Special Economic Zone (SEZ), near the border with Thailand.

Conservation and Livelihood Challenges

Declining fish populations

Figure 2: The sun sets on houses at Koh Sralao coastal fishing village in Cambodia (Photo: Furqan Asif)

Fishers have spoken about fish declines for decades(5) and continue to be concerned about fish stocks. The observations made by Koh Sralao fishers are consistent with statistics for the Gulf of Thailand which shows a dramatic decrease in catch per unit effort (an indirect measure of fish abundance) over the past decades.

The declines observed in Koh Sralao‘s aquatic resources may be due to a number of different factors. Fishers have observed an increase in foreign fishing vessels in the nearshore area. Thai fishing vessels may have moved into Cambodian waters as a result of Thailand’s fisheries reform(9). Fishers also talk about the impacts of climate change on aquatic resources. Although the direct effects of climate change on fisheries in Koh Sralao are not yet clear, it seems that rains are less predictable, and storms may be more frequent. Ocean warming may be impacting fish migration routes and reproduction(8).

Sand dredging

In addition to the persistent decline in catch, sand dredging, which began in the Koh Sralao area in late 2007, has had an impact on the aquatic resources surrounding the Koh Sralao community (Figure 3). The short term impacts of this dredging are clear(5):

- Fish habitat is being destroyed. Dredging deepens shallow channels, impacting fish and other aquatic habitat in the process.

- Fish migration routes are being disturbed, and the water is said to be more turbid.

- Boats have been dredging near the edge of the mangroves, partially damaging some trees and completely ripping out others.

Community Initiatives

Koh Sralao is a village with a history of community organization around resource management(5). This means that villagers have been able to organize formally but also use informal channels to express their concerns.

Figure 3. A barge carrying sand from sand mining operations in Koh Kong (Photo: Furqan Asif)

Sand dredging

Villagers have been concerned about the sand dredging since it began in 2007, and have been involved in protests, public consultations and meetings with sand dredgers. At one point the sand dredging came within eyesight of Koh Sralao, which mobilized villagers yet again. The Koh Sralao community has received support from NGOs, including an activist NGO that initiated an anti-sand mining campaign in 2015.

Mangrove conservation

The Koh Sralao community has worked together to safeguard their natural environment. They have become aware of the importance of conserving the mangrove forests that form a critical link to their livelihood. For example, annual mangrove replanting has become a community tradition since the late 1990s. The area is known for its mangroves which span 23,750 hectares in a protected area and features an ecotourism site set up near the Peam Krasop community.

Livelihood diversification

Households have responded to marine resource degradation by shifting livelihood activities within and beyond the village, with regional factory wage work emerging as another diversification strategy. It is predominantly young women in Koh Sralao that go to work at the Koh Kong SEZ located near the provincial town, since SEZ factories mainly hire women between the ages of 18 to 25(7). However, there is no maternity leave for women, and it is difficult for them to return to the SEZ after the age of 28. Thus, while young women are gaining more opportunities beyond the fishing village, such gains are time-sensitive, and it is unclear how many young women may return to the village at another point in their lives.

Meanwhile, a small, but growing number of men in the village have moved out of fishing-based livelihoods by leaving the village and finding work, either in Koh Kong town or Phnom Penh the capital. Most of this work is in the informal economy, but is seen as less precarious than fishing. Young men may be less interested in fishing, as fishing cannot consistently provide for their material well-being(2). The long-term implications on the lives and livelihoods of villagers in Koh Sralao are unclear. What is certain, however, is that it will depend partly on the future state of marine resources in coastal Cambodia.

Practical Outcomes

Sand dredging

One of the outcomes of the initial protests to the sand dredging was that the dredging activities moved to another area, out of sight of Koh Sralao. Even so, the community wanted the activity to stop altogether, since the negative impacts of the sand dredging continued to be felt. Community members worked with a local activist NGO, providing interviews to media and spearheading a social media campaign, to share the impacts of a decade of continuous sand mining on coastal livelihoods. In November 2016, the Ministry of Mines and Energy announced that they had halted sand dredging operations in Koh Kong, with a total ban on coastal sand dredging for export emerging in mid-2017(4).

The ban on sand dredging is certainly welcome news to the villagers and for the conservation of the mangrove ecosystem. More broadly, this story not only highlights the challenges of natural resource-based livelihoods and the pressures that coastal communities face (shaped by socio-economic and political forces), but also the importance and impact of grassroots community activism for coastal ecological conservation.

Livelihood diversification

Local factory labour opportunities continue to provide a higher, more consistent income than would otherwise be the case for most young women in Koh Sralao. Women are sending remittances home, and for these households this is an additional source of income (even if time sensitive), all the more important given the challenge of small-scale fisheries livelihoods (3). The longer term implications of such wage work, in the sense of helping to sustain coastal livelihoods and villagers’ well-being, remains to be seen.

References

- Asif, F. (2019). ‘From Sea to City: Migration and Social Well-Being in Coastal Cambodia’. In: A.G. Daniere and M. Garschagen (eds.), Urban Climate Resilience in Southeast Asia, The Urban Book Series, pp. 149–177. Cham, Switzerland: Springer. Available at: https://doi. org/10.1007/978-3-319-98968-6_8

- Asif, F. (2020). Coastal Cambodians on the Move: The Interplay of Migration, Social Wellbeing and Resilience In Three Fishing Communities [Thesis, Université d’Ottawa/ University of Ottawa]. Available at: http://ruor.uottawa.ca/ handle/10393/40420

- Horlings, J. and Marschke, M. (2020). ‘Fishing, farming and factories: adaptive development in coastal Cambodia’. Climate and Development 12(6): 1–11. Available at: https://doi. org/10.1080/17565529.2019.1645637

- Lamb, V., Marschke, M. and Rigg, J. (2019). ‘Trading Sand, Undermining Lives: Omitted livelihoods in the global trade in sand’. Annals of American Association of Geographers 109(5): 1511–1528. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1080/2469 4452.2018.1541401

- Marschke, M. (2012). Life, Fish and Mangroves: Resource Governance in Coastal Cambodia. Ottawa, Canada: University of Ottawa Press. Available at: https://doi. org/10.1017/s003060531200173

- Marschke, M. (2016). ‘Exploring Rural Livelihoods Through the Lens of Coastal Fishers’. In: K. Brickell and S. Springer (eds.). Handbook of Contemporary Cambodia, Chapter 8, pp. 101–110. London, UK: Routledge. Available at: https://doi. org/10.4324/9781315736709

- Narim, K. and Paviour, B. (2016). ‘Sand Extraction in Koh Kong Province Halted, Ministry Says’. The Cambodia Daily [website], 17 November 2016. Available at: https:// english.cambodiadaily.com/news/sand-extraction-koh- kong-province-halted-ministry-says-120637/

- Savo, V., Morton, C., Lepofsky, D. (2017). ‘Impacts of Climate Change for Coastal Fishers and Implications for Fisheries.’ Fish and Fisheries 18(5): 877–889. Available at: https://doi. org/10.1111/faf.12212

- World Fishing & Aquaculture (2016). ‘No more free rides – as Thailand reforms fisheries’. World Fishing & Aquaculture [website], 11 October 2016. Available at: https://www. worldfishing.net/news101/industry-news/no-more-free- rides-as-thailand-reforms-fisheries

Acknowledgements

We thank S. Songpornwanich and A. Ruksapol for their ongoing work with the villagers and for granting access to their field work results.

Community Conservation Research Network

Saint Mary’s University

Halifax, Nova Scotia

B3H 3C3 Canada

Phone: 902.420.5003

E-mail: ccrn@smu.ca