30 Jan Maya Zone, Mexico

Karla Diana Infante-Ramírez, Malloni Puc-Alcocer and *A. Minerva Arce-Ibarra El Colegio de la Frontera Sur, Mexico (ECOSUR), *aarce@ecosur.mx and aibarra@dal.ca

Key Messages

- The Maya Zone’s tropical rainforests in Quintana Roo state of Mexico provide many provisioning, regulating, cultural and supporting services.

- Both the government and the Maya people themselves have their own meanings of conservation and their own motivations for conservation.

- Community conservation initiatives must be part of national and international conservation programs.

Community Introduction

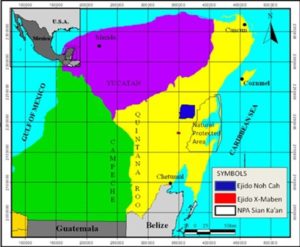

Quintana Roo’s “Maya Zone”, located in the Yucatan peninsula of Mexico, is a biocultural region with inhabitants who speak the Maya-Yucatec language in their daily lives. The Maya people rely on rainforest resources and agriculture as their main livelihoods. Maya communities also practice slash-and burn-cultivation (“milpa”) which is regarded as a cultural tradition. The communities are organized into common holdings called “ejidos”. Here we focus on the ejidos of Noh Cah and X-Maben (Figure 1), particularly their main towns (“Noh Cah” and “Señor”), with 86 and 3,095 inhabitants, respectively. In socio-economic terms, these communities are highly marginalized.

The Maya Zone is located in well-preserved tracts of tropical rainforest which provides a portfolio of ecosystem services1,2 to the users and communities dependent on it, including: a) provisioning services such as food (e.g., small-scale game, gathering of medicinal plants, and fish from water-filled sinkholes called “cenotes”); b) regulating services such as protection from hurricanes; c) cultural services such as using the sacred “cenotes” for baptism, and recreational inland fisheries; and d) supporting services including CO2 sink source.

The Maya people from these communities utilize these various services, and engage in conservation activities that help to maintain the services. The complex meanings they have for such conservation, as well as their motivations for conservation, are important factors in the social subsystem of the Maya Zone.

Figure 1. Study area in Quintana Roo´s Maya Zone.

Conservation and Livelihood Challenges

The Maya Zone area has been impacted by the effects of climatic variability (climate change). Over the last three decades, people in the communities have reported that rains have not arrived at expected times or in usual quantities. This has affected the productivity of traditional agriculture (“milpa”), a rain-fed system, resulting in insufficient harvests of staple foods to support local needs3. In addition to this challenge, several species are endangered in the region, for instance, the jaguar and the peccary, affecting biodiversity and the local residents.

In the 1990s, the federal government launched an international initiative on biodiversity conservation called the “Mesoamerican Biological Corridor”. However, that conservation program was based on a top-down approach, and hence did not (and still does not) take into account the kind of local conservation activities practiced by the local people. Being descendants of the ancient Maya civilization, and depending heavily on rainforest resources, people in communities of this area still actively look after those resources.

Community Initiative

Local authorities in the Maya Zone actively explore opportunities to receive support for environmental activities. A recent example was the possibility of applying for funding to a federal ‘payment for environmental services’ program. The local authorities recognized that many locals did not understand (from a Western-science perspective) what “an environmental service” was, and thus engaged with the CCRN-ECOSUR team to organize a seminar on ‘what is an environmental service’ and the ‘payment for environmental services’ program. Other seminars have been held, on topics suggested by the local residents and others suggested by the CCRN-ECOSUR team. Another was about “Climatic variability in the Yucatan Peninsula” (Figure 2) and addressed the influence of major weather events, for example the “El Niño Southern Oscillation” (ENSO), which affects mainly primary activities in the region.

These seminars aimed to improve the capacity of the communities in dealing with climate variability. This capacity building is being accompanied by monitoring of the Maya social-ecological system using indicators focused on climate variability and its impact on livelihoods, such as slash and burn-shifting cultivation.

Figure 2. Seminar presentation on “Climatic variability in the Yucatan Peninsula” delivered to inhabitants of Noh cah and “Señor” Maya communities by Karla Infante Ramírez (Photo credit: Karina Chale Silveira).

The capacity building activities that locals and community groups participated in also looked at the local meanings of conservation and motivations toward conservation. The results, presented back to the communities, provide feedback based on their experience and local knowledge (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Presenting results on the meanings of ‘Conservation’ back to Noh Cah inhabitants by Malloni Puc Alcocer. As local people from Noh cah prefer to discuss in the Maya language, Mr. Xool (red cap) worked in the research team as a translator (Photo credit: A. Minerva Arce-Ibarra).

Practical Outcomes

Understanding the meanings and motivations of the Maya people towards conservation is a complex subject. Research results indicate that there are two types of motivations for conservation in these Maya communities, namely extrinsic and intrinsic motivations. The former derives from government-based conservation programs, whereas the latter are people’s own motivations. According to Puc-Alcocer4, two types of conservation of the rainforest are in place in this region: one referring to the conservation programs implemented by the government and the other (the Kanan K’áax) which is a type of Maya community-based conservation. “Kanan K’áax” is a Maya phrase and literally means “to look after the rainforest” (Kanan means ‘look after’ and K’áax means ‘rainforest’).

Local Maya conservation initiatives that are in place need to be included in national and international conservation programs. Therefore, it is suggested that the improved understanding of Maya meanings and motivations for conservation reflected here be taken into consideration by conservation initiatives such as the “Mesoamerican Biological Corridor” and also by state institutions dealing with development programs in the Maya area and elsewhere in Mexico.

References

1. Millennium Ecosystem Assessment (2005). Millennium ecosystem assessment synthesis report. Island Press. Washington, D.C.

2. Infante-Ramírez, K. D. and Arce-Ibarra, A.M. (2015). Percepción local de los servicios ecológicos y de bienestar de la selva de la zona maya en Quintana Roo, México [Local perception of the ecological services and well-being of the Maya Zone’s rainforest from Quintana Roo, México]. Investigaciones Geográficas, Boletín del Instituto de Geografía, 2015(86), 67-81.

3. Bello-Baltazar, E. (2001). Milpa y madera, la organización de producción entre Mayas de Quintana Roo. Doctor of Science Thesis in Social Anthropology. Universidad Iberoamericana, México, DF.

4. Puc Alcocer, M. 2015. Conservación comunitaria de la selva maya en los ejidos Noh-Cah y X-maben, Quintana Roo. [Community-based conservation of the rainforest at the common holdings of Noh Cah and X-Maben, Quintana Roo]. Masters Thesis. El Colegio de la Frontera Sur. Chetumal.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to the Maya people and their local authorities for granting us consent to undertake research on their lands. Our main source of funding came from the SSHRC-CCRN project. We thank all the support received from Saint Mary´s University and CCRN staff. Partial support for our research came from ECOSUR and CONACyT fiscal funds. CONACyT also granted scholarships to pursue the graduate studies of K.D. Infante-Ramírez and M. Puc-Alcocer.