27 Sep Xai-Xai Region, Mozambique

Key messages

- People who practice traditional ceremonies of evocation of ancestral spirits inhabit rural communities in the Xai-Xai Region of Mozambique.

- Places where the residences of the founders of the communities were once located, currently host traditional ceremonies – i.e., these are sacred natural sites.

- The sacred natural sites are important for the local way of life, however, conflicting use of land and resources are negatively affecting their maintenance.

Community introduction

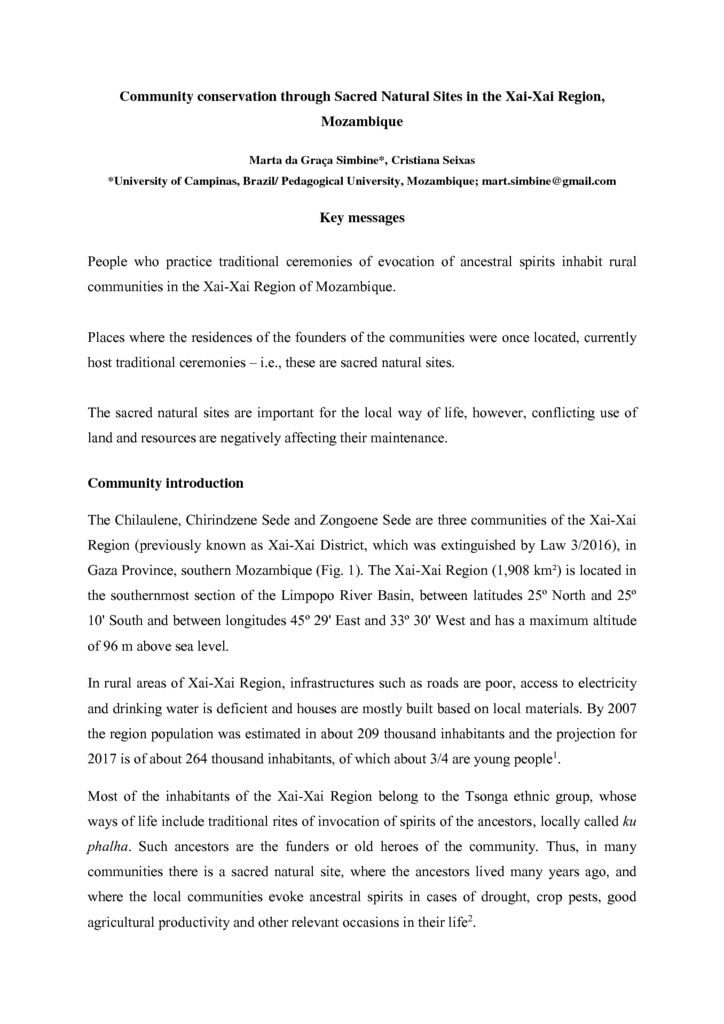

The Chilaulene, Chirindzene Sede and Zongoene Sede are three communities of the Xai-Xai Region (previously known as Xai-Xai District, which was extinguished by Law 3/2016), in Gaza Province, southern Mozambique (Fig. 1). The Xai-Xai Region (1,908 km²) is located in the southernmost section of the Limpopo River Basin, between latitudes 25º North and 25º 10′ South and between longitudes 45º 29′ East and 33º 30′ West and has a maximum altitude of 96 m above sea level.

Community conservation through Sacred Natural Sites in the Xai-Xai Region, Mozambique (pdf)

In rural areas of Xai-Xai Region, infrastructures such as roads are poor, access to electricity and drinking water is deficient and houses are mostly built based on local materials. By 2007 the region population was estimated in about 209 thousand inhabitants and the projection for 2017 is of about 264 thousand inhabitants, of which about 3/4 are young people1.

Most of the inhabitants of the Xai-Xai Region belong to the Tsonga ethnic group, whose ways of life include traditional rites of invocation of spirits of the ancestors, locally called ku phalha. Such ancestors are the funders or old heroes of the community. Thus, in many communities there is a sacred natural site, where the ancestors lived many years ago, and where the local communities evoke ancestral spirits in cases of drought, crop pests, good agricultural productivity and other relevant occasions in their life2.

The Gaza Province in the Southern Mozambique (A); The Xai-Xai region in Gaza’s coastal zone (B); Chilaulene, Chirindzene Sede and Zongoene Sede communities in the Xai-Xai Region (by Simbine and Ferreira).

In Chilaulene, Chirindzene Sede, and Zongoene Sede, there are people who have taken care of the sacred natural sites for a very long period. These are custodians or guardians of spiritual, cultural, and biological values, among others, of the sites – i.e., they have embraced the community responsibility for taking care of such sites. The custodians of natural sacred sites in the Xai-Xai Region are descendants of the founders of the respective localities2.

Chilaulene

The name Chilaulene means place of Chilaule and derives from the verb “ku laula” which means to elect, to choose, or to select in the local language Xichangana. According to the custodians of Chilaulene, that name is in honor of Sigode Chilaule, the man for whom the place was selected and who became the founder of the community.

Chilaulene is located about 14 km from the Xai-Xai city, with an area of approximately 33 km² and a population estimated in about 10.600 people. In this community, small-scale livestock rearing, artisanal fishing and paid work in the informal sector of the South African Republic (RSA) supplement the small-scale agriculture.

In Chilaulene, there is the Sacred Site of Chilaule (0.6 ha), which includes mostly herbaceous vegetation, with a few shrubs and sparse trees, and a marsh, whose custodians are the members of the Sigode Chilaule family.

A ceremony of evocation of ancestral spirits in the Sacred Site of Chilaulene.

Chirindzene Sede

The name Chirindzene derives from the word “rindza”, which means “waiting” in Xichangana language. This was the place where, in early 1800’s, the emperor of the then Gaza empire (Nhugngunhane) ordered his companions Tcheri and Matchecane to wait for his return from Maputo (Mozambique’s capital), where he fled from his enemies during a tribal war.

The village of Chirindzene Sede is located about 32 km from the Xai-Xai city, with an area of approximately 36 km² and a population estimated in about 2,400 people. In this community, small-scale livestock rearing, charcoal production and informal paid work in RSA are the alternative sources of income to small-scale agriculture.

The Sacred Forest of Chirindzene (60.5 ha) is guarded by the Matavel family members, which are descends of Tcheri3. This sacred natural site integrates a dense forest formation and a stream whose source is also located within the site. According to local informal rules, everyone can use the creek water and collect fruits on the ground without any restriction, but only duly authorized traditional healers can extract forest products, for medicinal purposes.

This sacred forest was used also to host the community celebrations of national commemorative dates or cultural festivities (folkloric ceremonies) (i.e., it served as an outside community center).

Zongoene Sede

Zongoene is the administrative name of the village of Barra de Limpopo also known by Ka Mhula. “Ka Mhula” means “place of Mhula”. According to the custodians of Zongoene Forest, this name became popular in honor to Chirhaminhane Mhula, the founder and first leader of the Zongoene community.

The community of Zongoene Sede is located about 52 km from Xai-Xai city, with an area of approximately 69 km² and a population estimated in about 18,500 people. Artisanal fishing, production of charcoal and tourism (working in local tourism agencies) are the main activities that complement the income that the community members obtain from the small-scale farming.

Zongoene Sede comprises five Neighbourhoods numbered from One to Five. In the Neighbourhood Five, the least populated and isolated from the others, we find the Sacred forest of Chirhaminhane Mhula (7.0 ha). However, there are two other smaller (less than 3 ha each) and less known sacred natural sites located at Neighbourhoods Two and Three.

According to the custodians of Zongoene, inside the Sacred Forest of Chirhaminhane Mhula, (Fig. 3) it was located the house where Chirhaminhane Mhula lived and where Portuguese soldiers killed him during the war of resistance to colonial occupation. In this natural sacred site, it is forbidden by local rules any extraction of natural resources, not even for medical purposes.

A view of the core part of the Sacred Forest of Chirhaminhane Mhula.

Conservation Challenges

The communities of Chilaulene, Chirindzene Sede and Zongoene Sede evaluate the state of conservation of their sacred natural sites based on the combination of factors, including the cleanliness state at the entrance; the forest size; density of trees; the size of the trees, existence of artifacts that signal spirituality; frequency of visits by people from outside the community; use for non-spiritual purposes, and respect for the local community rules (observation of management institutions). Below, we present the challenges for conservation of each of these sacred sites by considering these factors.

In all the communities, the spiritual invocation ceremonies tend to be modified from the traditional ways, due to the lack of financial means to cater for the expenses that a traditional ceremony entails or to facilitate the presence of visitors. There is also less and less adherence by local people to the ceremonies due to changes in the spiritual values of the members of the communities, caused mainly by the emergence of new religious sects or governance dynamics imposed by the formal governance.

Another challenge is that all sacred sites have vestiges of uses not allowed by local institutions, probably caused by inhabitants who are unaware of the sacredness or do not share belief in the sacredness of these sites.

Challenges for conservation in Chilaulene

One of the major challenges for the preservation of the Sacred Natural Site of Chilaulene relates to small-scale livestock farming. The lack of a properly organized cattle-drinking system forces herdsmen to lead their cattle to the pond that is part of the sacred site, causing its degradation. In doing so, they contribute to the weakening of the sacred vision that the community members have had over that natural monument, as it represents a non-spiritual use and therefore not accepted by local institutions. Watering the cattle at the sacred site pond has lead to the decreasing conservation status, and consequent diminishing local community awareness of the sacredness.

Another challenge emerged in 1976, a year after independence of the country, when part of the sacred site was converted into a community cemetery for the burial of community members. Moreover, not all the Chilaulene community members are aware of the existence of a sacred site adjacent to the community cemetery. This may be associated with a lack of artefacts that would signalise the sacredness of the place. Therefore, part of the portion that remained for ceremonies of evocation of the ancestral spirits nowadays holds graves of other people.

Challenges for conservation in Chirindzene

Many members of the Chirindzene community claim that the sacred forest guarantees water in the village and without it they would die of thirst. This conviction arises from the fact that the creek that emerges in the forest has been the main source of water until about five years ago when the government started drilling boreholes in the community. Before that, the management of the stream and its banks sought to ensure that the water remained sufficiently clean for human consumption. However, after the drill of boreholes, only a small fraction of the community uses the stream (and only to wash clothes). This has led to poor management and reduction of the water quality.

The community is also facing a reduction in actions that promote the visibility of the sacred forest, both inside and outside the village, threatening the perpetuation of local community lifestyles. This situation arises from two main reasons: the number of visits by national and foreign people as well as the number of celebrations of national commemorative dates or local festivities are diminishing.

Challenges for conservation in Zongoene Sede

There are alternative sacred natural sites at Zongoene Sede. Although the conservation status is very less favourable, their existence and the distance from the other residential neighbourhoods contributes to a significant part of the local residents not engaging in traditional ceremonies of the Chirhaminhane Mhula Sacred Forest.

Community initiatives

Despite the reported challenges, community members have been engaging in some initiatives to minimize them and to maintain their traditional ceremonies, which for a long time has constituted their way of life.

The traditional leaders of the Chilaulene community is taking the lead in the efforts of preventing the conversion of the entire area of the sacred site into a cemetery. In effect, the custodians of the sacred site have sought to avoid that new graves are established in the remaining portion of the sacred site, in addition to the appeals for the exhumation of the bodies buried in the portion already transformed into a cemetery.

In Chirindzene Sede, between 2002 and 2005, the local community, supported by the Community Association for Health and Development (Associação Comunitária para Saúde e Desenvolvimento – ACOSADE), implemented an initiative for conservation of the sacred forest of Chirindzene3. This initiative resulted in the delimitation of that sacred forest with Eucalyptus sp, placement of plates inscribing local rules (prohibitions) related to the forest (Fig. 4), as well as the construction of huts at the entrance of forest. These actions have had a good impact, since the whole community knows today about the particularity of that place. Under the same project, honeybee hives were built for honey production and generation of alternative income for community members but the lack of technical assistance led to failure of this activity.

In the beginning of the 2000s, the community of Zongoene Sede joined efforts to build a hut with cement and other more resistant materials replacing the previous one built with local material. In addition, in 2012 the community, in collaboration with the environmental authorities of Gaza Province, reforested with Eucalyptus sp at least ¼ the forest area previously deforested.

Plate with the prohibitions related to The Sacred Forest of Chirindzene.

Practical outcome

The above context describe here has resulted from the first attempt to register the rules and context underlining natural sacred sites in Mozambique – a country with deficiency in several ecological, social and anthropological data. Through this research, we found that most of the challenges to the conservation of the sacred sites are potentially minimized by raising awareness of the existence and importance of sacred sites among all community members and empowering the local communities, and in particularly the custodians, to deal with pressures posed by government. We understand that the questions posed by the research is a first step towards increasing awareness on sacred sites, and we hope that this first contact with custodians of sacred sites, may reverberate in future collaboration with external actors.

References

1. Instituto Nacional de Estatística (INE) 2010. Projecções Anuais da População Total, Urbana e Rural, dos Distritos da Província de Gaza 2007 – 2040, Maputo

2. SIMBINE, M. G. Z. Florestas Sagradas Como Potenciais Zonas de Uso e Valor Histórico-Cultural em Moçambique. Doctorate project in Ecology, Instituto de Biologia, Universidade de Campinas, São Paulo (Dissertation in prep)

3. SIMBINE, M. G. Z. Factores Antrópicos e Conservação da Floresta Sagrada de Chirindzene, Gaza – Moçambique. 2013. Dissertação (Mestrado em Ecologia Ambiente e Território) – Faculdade de Ciências, Universidade do Porto, Porto.